10′ animated documentary by Ana Cristina Pereira

Não tem registo civil. Está encarcerado desde 1984. Tentou roubar o apuro ao condutor de um autocarro. Considerado inimputável, cumpre uma medida de internamento que ameaça eternizar-se. Vezes sem fim, percorre corredores que conduzem a corredores que abrem para a cela, a cantina, a enfermaria, o pátio ou o perímetro da prisão. Só sai com voluntários, que o levam aos mesmos lugares e a quem sempre pede um rádio. É como se tivesse sido apanhado num loop.

An animated documentary that, through the perspective of its residents, guide us on a journey to an unique place in Portugal: the psychiatric ward of the Santa Cruz do Bispo prison. A depository of people judged not accountable due to their mental disorders. The look of a man who has been living there, imprisoned, for 33 years, who has no identity card and receives no family visits: “the man who does not exist”.

I heard about “The Man Who Doesn’t Exist” from the voice of the director of the Santa Cruz do Bispo Prison, Hernâni Vieira. I was intrigued by the idea of men being imprisoned for over 30 years in a country with a maximum sentence of 25 years. I asked him to help me get to them and he mentioned that and other men considered unaccountable.

Vicente had been incarcerated since 1984. And, unlike everyone else, he had no civil identification number, social security number, taxpayer number, National Health Service user number, voter number. Not a single family member wrote to him or visited him. Only every three months would I go out for a few hours with Cláudia Assis, a volunteer from the Foste Visitar-me association, and another volunteer. He was, as Hernâni Vieira called him, “The Man Who Doesn’t Exist”.

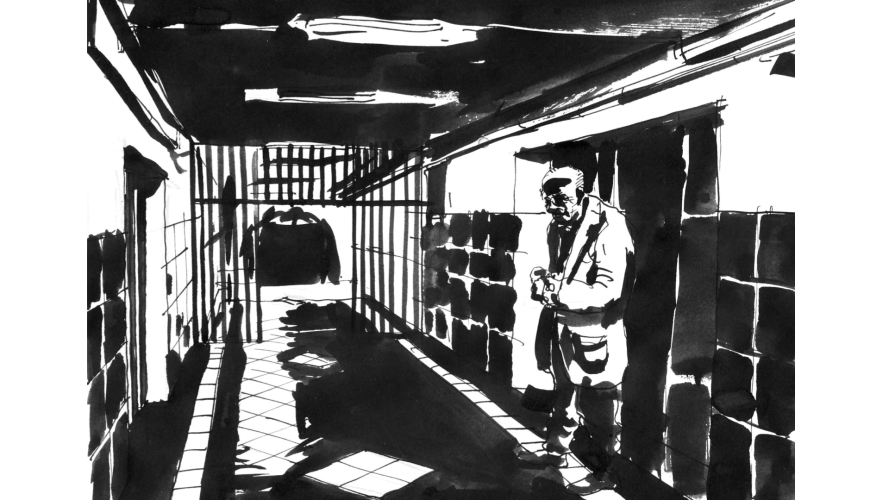

For a month, once a week, I and a colleague, photojournalist Paulo Pimenta, went to that part of the prison in an attempt to understand who these men were, how they interacted, what they had to say. Vicente was an extreme case of what the anthropologist and sociologist Erving Goffman long ago called a “total institution.” He felt good in there. Despite the overcrowding, despite the lack of doctors, nurses, medical assistants, re-education technicians, guards, despite the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment having drawn attention several times to abuses there committed. Despite the lack of visitors. There was a joy about him that was disconcerting.

It was necessary to find alternative ways to uncover that microcosm. Now, animated cinema allows us to humanize these people who are distant from the rest of the world, which tends to think of them as monsters and not as the people they are. I presented the idea to Animals, who immediately embraced it. Having obtained financial support from the Cinema and Audiovisual Institute for the development and authorization from the General Directorate of Reinsertion and Prison Services to enter what was one of the most inaccessible places in the entire Portuguese prison system, the team advanced to the field.

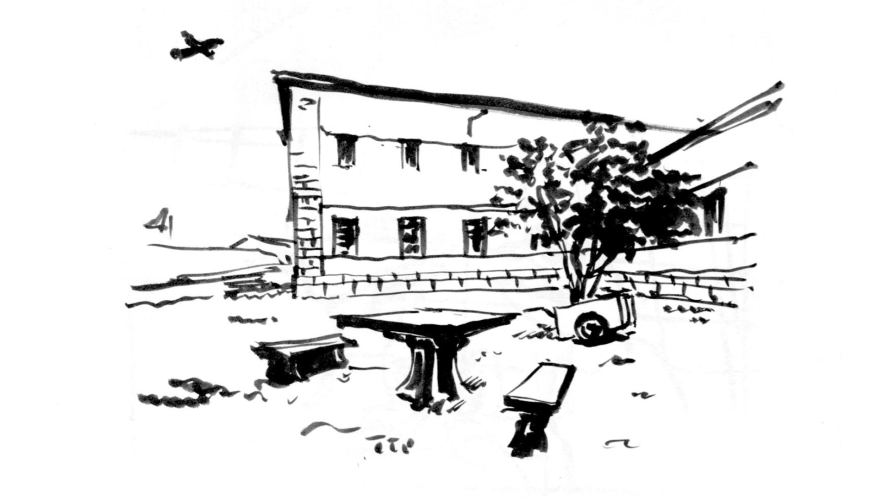

There was time to observe and collect images and sounds of life in that place, but also to interview Vicente, the psychiatrist, the psychologist, the occupational therapy technician, the director, the head of the guards and follow one of his precarious exits, with the association You went to visit me, to Vila do Conde. And to think.

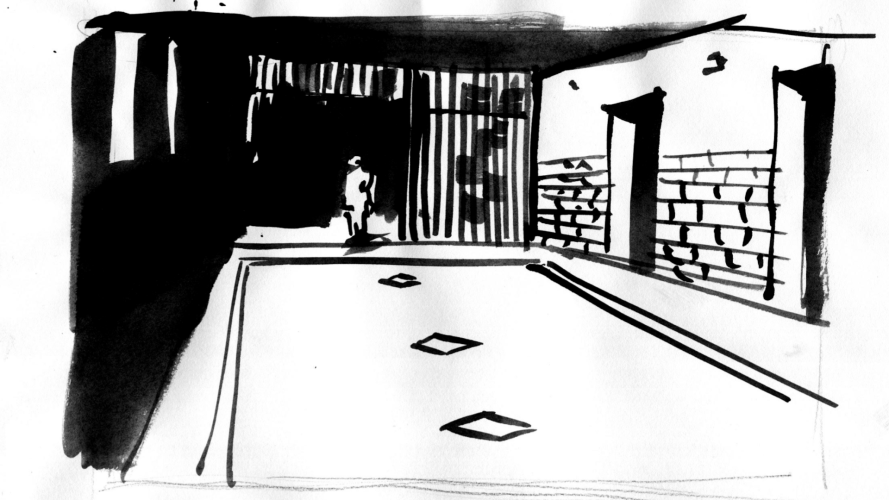

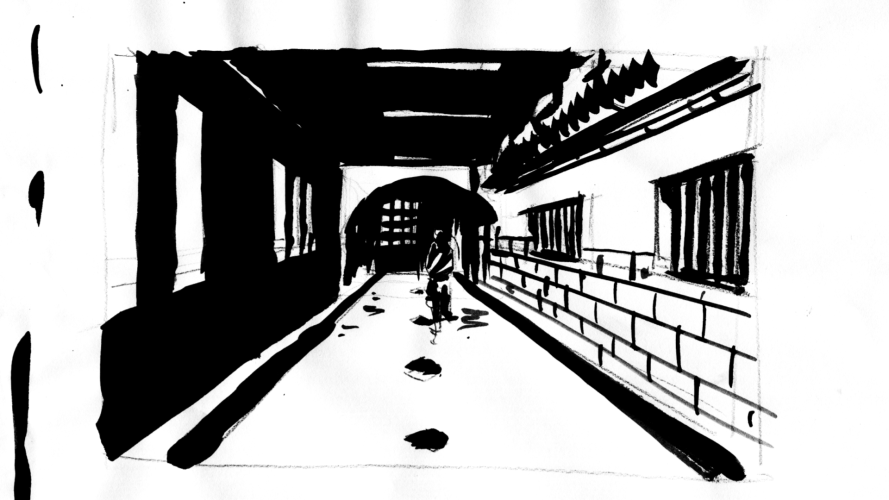

The winding, constant and recurring route that Vicente takes in his daily life, from his cell to the different spaces of the psychiatric clinic, constitutes the narrative thread of the film. In a subjective camera recording, we observe Vicente in his daily life, revealing his routines and his relationship with others (the inmates, the guards, the technicians, the volunteers). It’s like being in an impossible maze. The labyrinth represents both the context in which he finds himself (almost) of his own free will (he refused the chance he was once given to stay in a psychiatric hospital), and his mental inability to aspire to more (which guarantees him coffee, cigarettes and radios ), such as society’s inability to deal with these types of cases. On the one hand, the system cannot (does not try?) to find Vicente’s family history; on the other hand, it cannot place him in another type of institution with a potentially better quality of life.

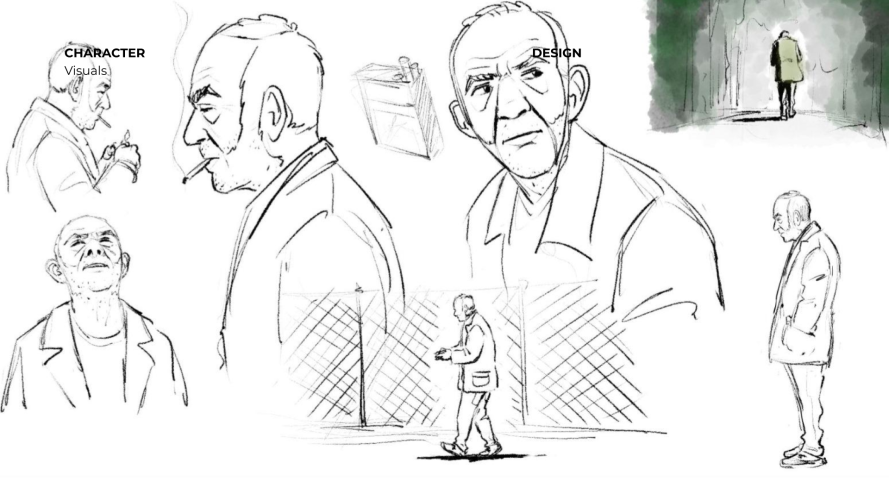

Their “tics” (such as rubbing their hands or straightening their hair), their disproportionate clothes (from the donation closet) and their preferences (radio, tobacco, coffee) enrich the scenic space. They reinforce his double status as a prisoner (physical prison / mental prison), although the system does not recognize him as a prisoner, it assumes him as a patient. The natural/original ambience creates a sound atmosphere that amplifies the sensation/perception of that universe.

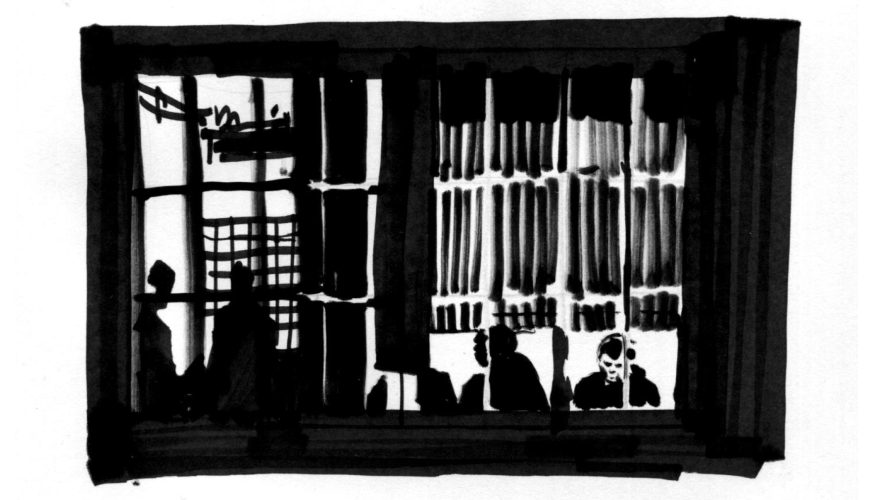

Throughout the film, Vicente’s voice is the only one that matters. All the others around him transform into more or less diffuse figures. It is the (possible) rescue of Vicente’s right to be, to have a voice, to tell his own story, to express his thoughts about freedom and confinement, life and death. Without any instruction, sometimes it even seems like he writes poetry with his mouth, as journalist and writer Elaine Brown would say. The use of the subjective camera, which seeks this personal vision, allows an almost game of hide and seek, which alludes to the invisibility to which Vicente has been subject his entire life. Although he is the undisputed protagonist, he is almost only seen in glimpses or reflections in mirrors or shop windows. There are few moments when the camera lets go and shows him. And these take place in a different space-time from the labyrinth where most of the action takes place.

This is a reflection that we believe is important to make, especially now that the country is preparing to mark 50 years since April 25, 1974.

Ana Cristina Pereira [author, scriptwriter and director]

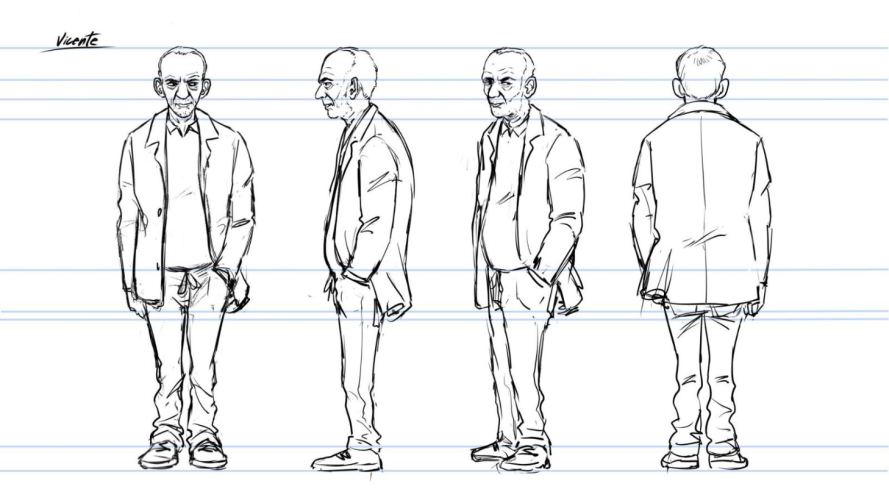

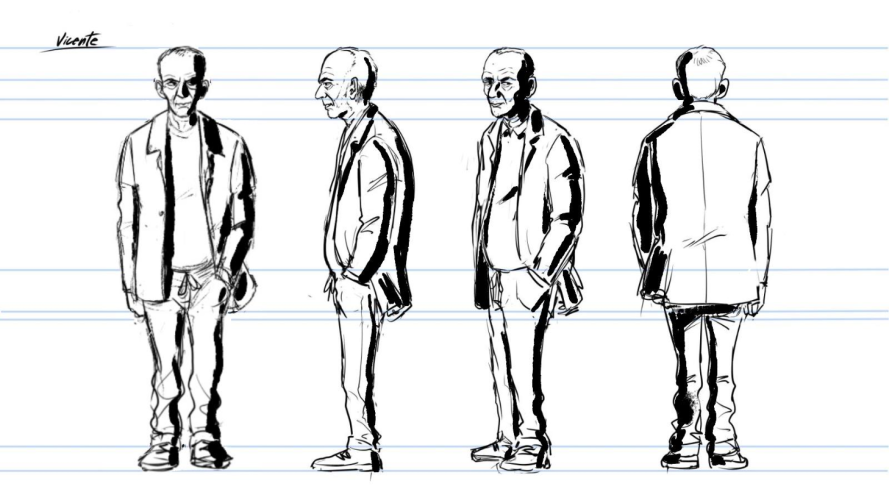

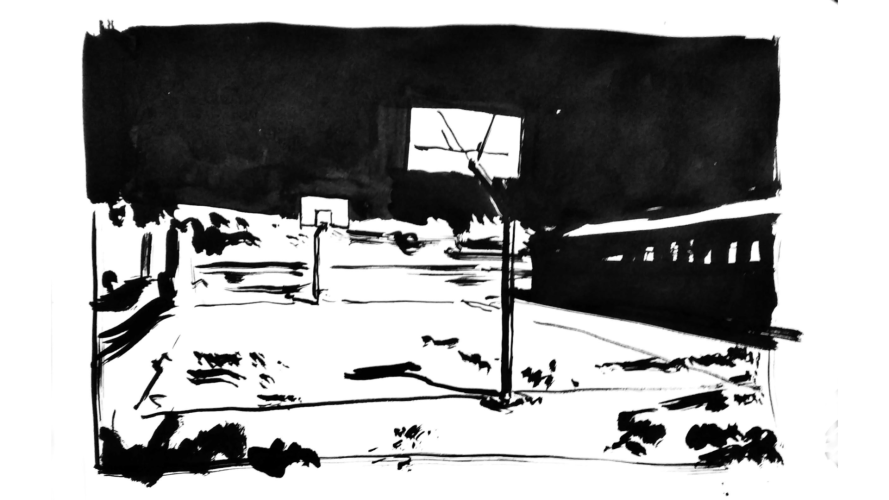

Este projeto, que recorrerá à animação tradicional 2D, convida à utilização do contraste como forma de estabelecer distinções entre o fora e o dentro, o eu e o outro, o passado e o presente, a realidade e a imaginação. Como este será um olhar exterior e a compreensão da realidade alheia é sempre turva, em termos gráficos o filme andará entre a singeleza das linhas, indefinidas – como se fossem fragmentos de sonhos – para depois concretizar e definir o contexto e a ação; e o alto-contraste expressionista, também de forma gradativa, de um particular indistinto, casual, para o concreto.

Estas abordagens resultarão numa quebra entre a suavidade desse lugar um pouco mais “normal”, embora fragmentado, para um outro, que terá a ver com as situações em que o encarceramento esteja mais exposto. Em termos gerais, esse contraste que se deseja alcançar, será limitado pela ausência de cor, sublinhando assim os múltiplos níveis de confinamento e exclusão que esta situação revela.

Estas abordagens gráficas, instáveis por natureza, pretendem dar também substância às caracterizações física e psicológica, uma vez que idealmente serão informadas a partir das descrições que Vicente faz de si próprio e das rotinas que o moldam e definem.

A construção da narrativa animada assentará na fluidez dos espaços, ações e movimentos conducentes à construção e definição de cada cena, como se o espaço e o tempo se fossem construindo diante do espectador ao ritmo das estórias do protagonista e do seu deambular dentro e fora das paredes que habita.

Apesar de nos apoiarmos nas rotinas e na repetição das ações para a construção da narrativa, esta será desenhada de forma a que se perceba um trajeto semelhante a um labirinto, ou a um jogo circular, de onde ninguém sai.

Para isso, os movimentos de câmara ou as metamorfoses animadas darão uma sensação de percurso contínuo, por vezes num ritmo suave e pacificado, por vezes desconcertante, outras vezes luminoso, como que em procura de alguma identidade ou filiação e o momento efémero dessa realização. Este movimento será contrariado por obstáculos, pedaços do lugar do confinamento que, mais tarde, perceberemos como fazendo parte da estrutura do tal labirinto.

O contexto de reclusão e a sua especificidade são dados gradualmente, à medida que estes obstáculos se forem instalando com maior frequência e presença. Se “O Homem que Não Existe” até um certo ponto existe como todas as pessoas através de experiências que vai relatando (banais no contexto do ser humano como um ser social, relacionadas com a patologia que sofre e com os actos que cometeu), está privado da mais básica identificação pessoal e não tem família que o testemunhe.

Referências de cinema animado: Toccafondo, Bruce Bickford, Georges Schwizgebel, William Kentridge, Simone Massi

Budget: 156.600,00 €

Secured financing: 90.000,00 €

DOSSIER [PT] DOSSIER [EN]